A Parallel Reality

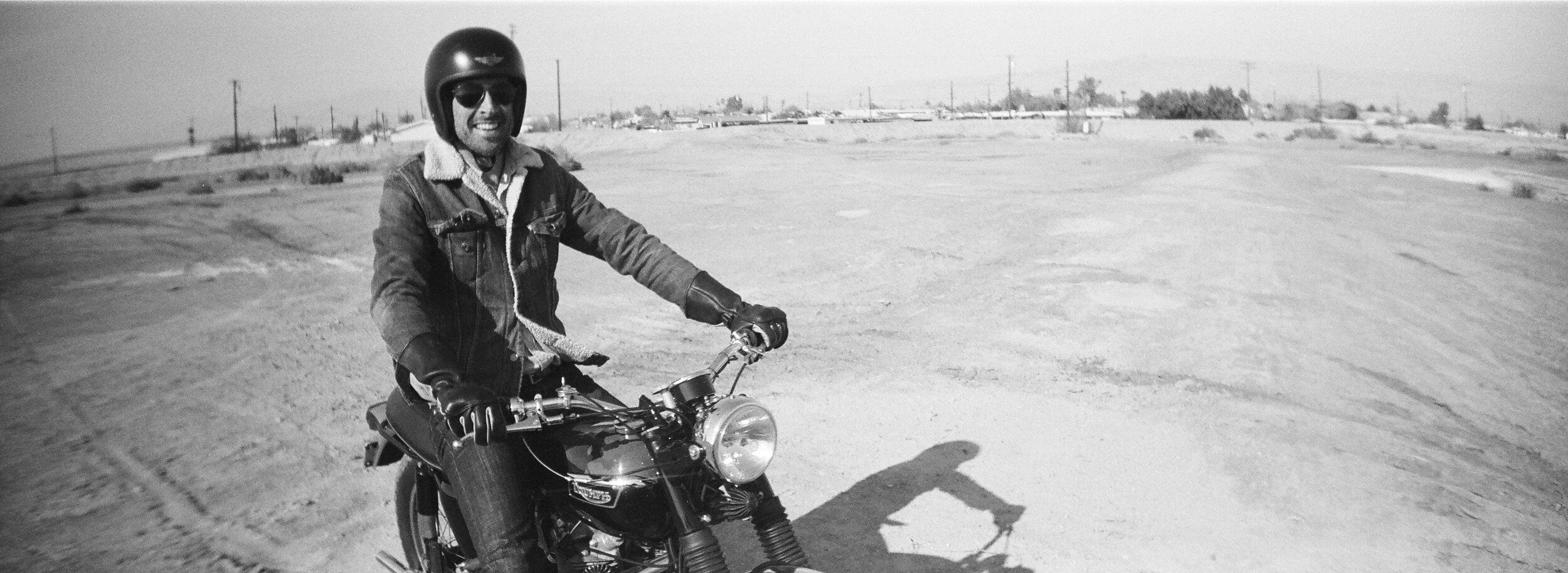

Words by Hugo Eccles | Photography by Aaron Brimhall

Hugo Eccles is co-founder and design director of Untitled Motorcycles, a company based in San Francisco and London that designs and builds custom motorcycles for both private clients and factory brands like Ducati, Moto Guzzi, Triumph, Yamaha and Zero Motorcycles. He’s also a professor of industrial design. Below, he examines the design approach to a recent build for Zero Motorcycles.

When Zero Motorcycles approached me with a potential project, we’d been dancing around each other for a while. I’d moved to San Francisco in 2014, and soon after began reaching out to electric motorcycle companies like Mission, Energica, Alta and Zero and asking for test rides. Northern California, after all, is the epicenter of the electric vehicle industry in America. Riding the Mission R, Alta Redshift, Energica Ego and Zero SR were the first truly new motorcycle experiences I’d had since the groundbreaking Honda CBR900RR Fireblade ushered in the era of the superbikes in the early Nineties. The experience ignited a burning obsession to build an electric motorcycle.

One morning in May 2018, I received an enigmatic email from my contact at Zero: “We may be entering a window of opportunity to work on something unique and cool. ...” I don’t think it really hit me until I was being escorted through a series of security doors to the workshop at the heart of Zero’s Scotts Valley headquarters. They were offering me exclusive access to their SR/F, two years into development, and still some ten months from public launch. I would be the first and only designer-builder in the world to get their hands on Zero’s brand new motorcycle.

Fuck yeah.

My background is somewhat unusual for the motorcycle world in that I’m neither a trained mechanic nor an automotive designer. I studied industrial design at the Royal College of Art in London and have worked on everything from consumer electronics for household brands to watches for TAG Heuer and Nike, to concept cars for Ford. My design training informs my approach to building motorcycles. For starters, I’m conscientious about not being dogmatic about what a build is going to be until I’ve got a clear idea of what I’m working with. Typically, before I do anything – sketches, study models, anything – I’ll strip a motorcycle down to its rolling chassis of frame, engine and wheels. That done, I can study the lines, understand what relates to what, see where there are natural intersections, and get a sense of the spirit of the machine. I’m asking the motorcycle what it wants to be.

Once I’ve got a handle on this, I can begin to reshape the motorcycle by what I add back. This approach works well with combustion machines because, inevitably, there are a number of elements that you have to replace – fuel tank, carbs, exhaust and so on – and these are all opportunities for redesign and reduction. An extreme example of this was the process of designing the Hyper Scrambler, which I’ve only half-jokingly described as continually removing components until the motorcycle stopped working and then reinstalling that last part. It’s not that far from the truth. Lotus Cars founder Colin Chapman said it much more eloquently: “Simplify and add lightness.”

However, as I soon discovered, this isn’t necessarily a useful methodology with an electric motorcycle. Once I’d taken off all the SR/F’s plastic parts, I realized that none of them were truly required to make the motorcycle function. An electric motorcycle doesn’t need any of those traditional elements since there’s no fuel and no exhaust. There’s a “gas tank,” but it’s really just a storage compartment and not essential to the functioning of the machine. So, if you don’t need any of these things, what do you need? Had I just intellectualized myself out of a project?

In my 25 years as a designer, I’ve never met a problem I couldn’t solve, but I’ll admit there was a moment when I thought, “I’m going to have to go back to Zero and tell them, sorry, there’s nothing meaningful I can do here.”

Then it dawned on me: I’d been looking at the problem all wrong. I didn’t need to redesign the SR/F – I needed to un-design it.

Our ideas of motorcycles are based on the constraints of the internal combustion engine. With the introduction of electric, those constraints and those “rules” disappear. It’s no longer a matter of technical limitation but of a belief limitation. I could rewrite the rules. It was a unique opportunity – maybe a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity – to completely reimagine a motorcycle from the ground up.

Although I didn’t yet know what I did want to do, I had a clear idea of what I didn’t want to do. Most electric builds that I’d seen mimicked traditional combustion motorcycle tropes, which seemed to be a redundant exercise. Why put a “gas tank” on an electric motorcycle? Why make an electric bike look like a gasoline motorcycle at all? It made no sense to me. Style-wise, electric motorcycle concepts generally seem to fall into one of two camps – either retro-nostalgic or expressive-sculptural – and I wanted to avoid both because, to my mind, they’re merely superficial styling exercises that sacrifice functionality for esthetics. So much more is possible.

One thing I knew for certain was that the end result had to be unmistakably electric. It would celebrate what makes an electric motorcycle unique instead of hiding it apologetically behind bodywork. I wanted to use an industrial designers first principles approach to create an entirely new visual language for this new category of electric. With most electric motorcycles, little of the form prepares you for the very different experience that you’re about to have.

If the motorcycle resembles a conventional motorcycle, you’re naturally going to expect a conventional riding experience.

But nothing could be further from the truth, and I felt that the visual language needed to communicate that this was going to be a very different experience.

When people think about electric they naturally think about the future, but I started my design process by looking backward. From the mid-1880s onwards, there was an explosion of ideas about motorcycles – no industry standards had been established, and every motorcycle company had their own opinion on what this nascent technology should be. This set me thinking about a modern motorcycle from an alternate reality where, instead of developing gasoline motorcycles for the past 140 years, the industry had been developing electric motorcycles. What would an electric motorcycle from this parallel 2020 look like? Dragged across from one timeline into another, it would simultaneously be both familiar and unusual. That’s what I set out to create with the XP – not a future reality, but a parallel one.

Without the limitations and constraints of internal combustion, a motorcycle from this parallel 2020 could be much simpler, with fewer components. This parallel reality would be constrained by the same rules of physics, not to mention similar economic realities, so things like conventional forks would remain for expediency and practicality.

I’d had a couple of test rides on the pre-production SR/F and was blown away by the sensation. The linear and continuous delivery of power – the SR/F makes an astounding 140 foot-pound of torque and has no gearbox –

[it] felt like piloting a small jet, so trying to embody that experience felt like a good design direction.

Earlier experiments had confirmed that almost no traditional bodywork was necessary on an electric motorcycle apart from surfaces that the rider could grip with their knees for control. That insight started me thinking about “control surfaces” – both human and machine. Human control surfaces would be typical things like foot pegs, heel guards, seat, knee pads and handlebars. Machine control surfaces would be aerodynamic panels, venting and so on.

Guided by this concept, I gathered and organized hundreds of images of experimental aircraft, WTAC cars, Moto GP bikes, winglets, canards, diffusers – anything and everything that inspired me around ideas of control, speed and aerodynamics. After a few weeks of intensive work, I had approximately five hundred pages of sketches and an overall design direction I was happy with. The motorcycle would consist of two main visual elements: an electric core comprised of the batteries, motor, controller and charger; and an analog chassis supporting the suspension and body panels. The seat would be integrated into the central powertrain to give the rider the impression that they were literally sitting on the “engine” of the motorcycle. The structural frame would feature “floating” aerodynamic panels held away from the tubework. The XP would be, literally and figuratively, a deconstructed motorcycle.

In parallel to developing the physical form, I also continued to develop the motorcycle’s story. If it was from an alternate present, it would also, logically, have an alternate past. The aerodynamic influences suggested that it might have a racing history – perhaps a retired track bike that had been retrofitted for regular road use. This idea of retrofitting gave me latitude to attach roadgoing elements in a more natural manner, not unlike the way headlights are installed on endurance racers. Similarly, the tradition of painting prototype race bikes in plain colors started to sync with an emerging idea of using an aerospace-spec coating to reflect the motorcycle’s experimental nature. I eventually settled on Aerospace Material Specification “Ghost Gray,” a government-standard color assigned to U.S. Navy experimental aircraft.

Paint colors aside, there’s something inherently ghostlike about electric motorcycles. Although on the surface a small difference, the dual nature of electric motorcycles – simultaneously both analog and digital – fundamentally changes the essence of the motorcycle. No longer is the motorcycle just a passively inert machine, but actively animate technology. I wanted to create a distinct and recognizable difference between the XP’s inactive and active states. When inactive, the almost monochrome motorcycle appears colorless and “dead.” When approached, the motorcycle recognizes its rider, illuminates its panel edges, and becomes “alive.” I suppose it’s an occupational hazard, but

I’ve been thinking a lot about the future of the motorcycle industry. I wonder about the direction it’s headed, and who will be the ones to steer it there.

Some traditional motorcycle manufacturers seem dangerously complacent, repeating the same old methods but somehow expecting different results. Exploring new territory inevitably upsets the status quo, and potentially customers in the short term, so most manufacturers aren’t willing to take that risk. When the original iPhone launched 14 years ago, nobody could have anticipated that an untested phone from a company with no telecoms experience was about to change the world so dramatically. Fourteen years forward from where we are now is 2034 – a time when many analysts predict that autonomous electric vehicles will be the predominant mode of transport. It’s possible that smaller, more nimble electric companies like Zero will lead the way, or perhaps, like in 2006, an adjacent industry will once again disrupt the orthodoxy with entirely new thinking.

So far, the response to the XP has been overwhelmingly positive. It’s taken a while to get here, but more riders are coming around to electric and many, like me, are excited to see where it can go. The “XP” moniker comes from the idea of an “experimental platform” – a fully functioning prototype capable of being developed for production. As well as being a technical platform, the XP is also intended as a figurative platform for dialogue about the future of electric motorcycle design. Ettore Sottsass once stated that “design is debate,” and, in that spirit, the XP isn’t supposed to be the final word but the opening of a conversation. Is the XP what electric motorcycles should look like in the future? I don’t have the hubris to assume that I can answer that. What I can say is that the answer is far less important than the fact that the question is finally being asked.