VOLUME 028 / WINTER 2022

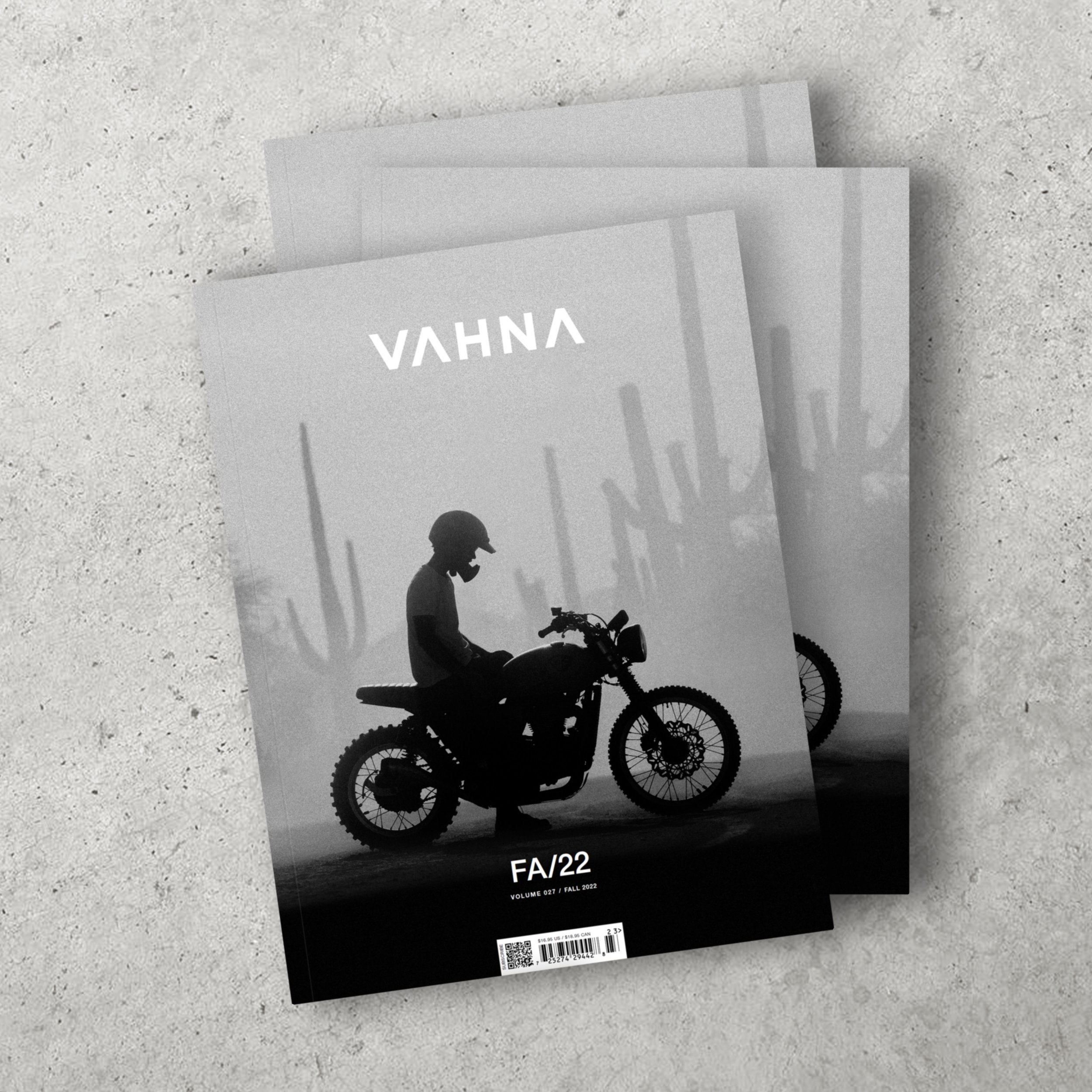

Words & Photo by Ben Giese

And so it goes on those days when the demons begin to creep in. I pull the bike out of the garage and strap on my helmet. Slip on some gloves, adjust the goggles and start up the engine. I feel the roar of the beast beneath, rumbling and ready to carry me away to god-knows-where.

The plan always starts out as a few relaxing miles to get some wind on my face and clear the mind, but soon enough I find myself on the outskirts of town where those lonesome backroads call my name. Wide-open prairielands with a road that leads through the vast and desolate rolling hills as far as the eye can see, twisting and curving to infinity. No cars, no cops, no limits. Just the type of freedom that could get you into some real trouble.

As I turn off the pavement and onto the long stretch of dirt ahead, the rear tire spins and kicks up rocks through first and second gear. I click it into third, and that’s when she really opens up to breathe…thirty-five, forty-five, fifty-five as I shift into fourth. Only a few inches beneath my feet the gravel road whizzes by in a blur, but my eyes are focused ahead. Faster…sixty, seventy…the engine growls, and the wind is now howling in my face trying to rip me off the back of the bike. But to outrun the demons I keep pushing it into fifth…seventy-five, eighty-five, ninety…and now I’ve got a white-knuckled grip on the handlebars as they vibrate up my arms, and I tuck my head for speed.

It’s a dangerous game we’re playing here. Walking the tightrope between nirvana and disaster, with no margin for error. But that’s when things really start to get interesting. The turbulence of the mind begins to calm, and all the noise of modern life becomes quiet. Regrets of the past, worries of the future, anxieties, loneliness and the fear of death. Those demons…they all fade into the background in a cloud of dust as your body tunes into the present. It’s like that momentary state of enlightenment that monks and mystics spend a lifetime chasing.

I’ll linger here as long as I can…but there’s a curve approaching, so I let off the gas, take a deep breath and let out a sigh of relief. I think I found what I was looking for. It’s time to head back home.

To be alive and to be a human is to feel pain and suffering. But when we can find a means to simply let go and exist purely in the here and the now, we can feel some peace of mind. Traditionally, people search for it through various forms of meditation, but for some of us that kind of clarity comes along only in these precious moments of chaos. I think that’s what drives big-wave surfers and free-solo climbers. And it’s what I love about fast motorcycles. Because when you find yourself balancing on that razor’s edge of mortality, all the rest becomes dust in the wind.

Darkness will always be looming in the background, somewhere in the distance, just around the bend. But at least we can have faith in our motorcycles to keep us grounded, to give us courage and perspective, and to light the way in the face of our demons.