BEAUTY AND PAIN IN THE COAST MOUNTAINS

Photography by Tyler Ravelle

BEAUTY AND PAIN IN THE COAST MOUNTAINS

Photography by Tyler Ravelle

NOTES FROM THE ROAD

Words by Alex Foy | Photography by Tal Roberts

I awoke the day of our departure with a healthy dose of hype churning in the gut and questions percolating that only the road could answer. Was my gear all dialed in? How efficiently could I pack a van? And where in the fuck is my spare socket wrench set?

Thoughts like these seem inevitable before a trip and hold some value before you hit the road. Best-case scenario they make you consult and reconsult the checklist, but left to run rampant, these questions will leave you rudderless and intimidated. Moral of it: Triple-check your gear and then burn it down the asphalt – your questions will be in the rearview as soon you hit 60.

After packing up I headed over to my friend Willis Kimbel’s spot to link with everyone. Pulling up at 10 a.m., I wasn’t surprised to see that the front yard was already divided into tidy rows of camera gear, camp items and quivers. The bike trailer was parked neatly next to the curb.

We had an all-time crew consisting of skateboarders Willis Kimbel, Jeremy Tuffli, and me, accompanied by videographers Elias Parise and Chris Varcadipane, and photographer Tal Roberts. Piper, Kimbels’ border collie, would also join for good measure. There wasn’t a dude in the van whom we hadn’t known for more than a decade, and that friendship certainly made chomping down the miles that much more enjoyable.

We weren’t skimping on the toys, either. Final count totaled at three dirt bikes and 12 skateboards in a variety of shapes and sizes to cover any terrain we might find on the road. The tiedowns were locked and double-checked, Piper’s vest was buckled, and the coolers had ice. We budgeted two hours to pack, we expected three, and were on the road to a bowl in the hills of Klamath Falls just before noon.

It’s a coin toss if the body and mind will cooperate on your board after a five-hour drive, but the terrain had everyone hyped to skate. Built in the early 2000s by Dreamland Skateparks, the deep moonscapes, one-of-a-kind features, and endless pool coping have made this place a must-hit for two decades now. The temperature also dropped below 90 degrees for the first time that day, and the music blasting out Willis’ speaker amplified the hype. We rolled until the sun went down and the transitions became gray and shadowed. Any more grinds would ha’ve been greedy.

A dropped pin and some enigmatic texts from an elusive old friend, Rye Clancy, led us through a dark, winding road to his homestead above Klamath. That night after setting up tents on his property, we wandered through his little slice of paradise with head lamps adorned, and in the shadows, we found two bowls built into the steep land, along with several small structures and sculptures. It’s his own personal playground, and it contains everything he needs to be happy.

By 7:30 a.m., we could already tell this day was going to be even hotter than the last. I rolled out of my van sweating like Ace Ventura crawling out of the rhino, and we knew we had to get the session going quickly before the heat passed into the triple digits.

Clancy’s bowls were rawer in the daylight. Traditionally bowls have either circular steel or pool coping on the edge of the transition. Clancy, however, bucked the system and cemented river rock into the bowl’s edge for his coping. Each grind raddled and ripped across the rocks, with debris flying out on each turn. When the rocks started flying, Kimbel got a strange idea. Gathering some spare stones from the property, he placed several on the rim of the bowl. His next frontside turn sprayed rocks across the ground like a surfer slashing through the edge of wave. In fact, some waves would have felt good in that moment as the sun continued to scorch down on us, so we jumped back in the van to crank the A/C and continue onward toward Mammoth.

A bit before the gas started burning on this trip, Kimbel caught up with his pal Jamie Lynn and rinsed a pint over recent travels and rambles to be, and Lynn gave Kimbel some hints for turns to take on this route. It’s impossible to give someone like Lynn a title. Artist? For sure. OG Pro Snowboarder? He’s done that. But Kimbel thinks of him more as a Renaissance man living life in a savage purity. He said meeting Vic Lowrence, aka “Sick Vic,” was a must-stop in Tahoe, and that was all we needed to hear to crank it west and make another detour.

Tahoe was never a part of the itinerary, but when Lynn made the connection and Lowrence hit up Kimbel about skating his private ramp in the woods, we just had to go. Traveling has taught us one rule that never ever seems to fail: Skateboards are the skeleton key to cool shit. I can’t even count the number of times I’ve encountered the most amazing people and most protected scenes simply because I had a skateboard and sense enough to bring some brews. And it’s no coincidence I’ve met my very best friends through skateboarding.

“Stay wherever we land and we’re good” was always the plan, and when Vic and his wife Sarah Lowrence gave us their yard for the night, we all felt the unspoken code of the road. There’s an understanding that goes both ways when you find people who share a common passion for what you do. A basement floor or a bit of grass might as well be a 5-star hotel after cramming a month of fun into one exhausting day. And the people who extend that hospitality know it just helps us along to the next realm of good times.

Lynn told us that Lowrence is a doer of all things fun and fast, and he’s gnarly as fuck at it all. Sure, he scaled the pro snowboarding ranks, but we soon came to find that he can hold his own on any type of board, bike, or sled. We had planned to crash with him that one night only, skate his ramp in the morning, and then head south that evening, but that piece of grass under the balcony and Lowrence’s lust for life kept us around wanting more. Two days later, we finally found ourselves saying goodbye to them after multiple backyard ramp and pool sessions, river dips, and late-night stories. I took a step back as we sat fireside laughing our asses off with our new friends and realized that this trip was kicking into high gear. Meeting people like this is why keeping rolling down these roads.

We arrived at the high-elevation oasis of Mammoth late that evening. It was a long and lonely road from Tahoe, but FuBar clips and two-way radio banter kept us pushing through the dark. Despite pulling into town close to 1 a.m., our next host and friend, Tom Weniger, met us outside the motel he manages as soon as we pulled up. People in the know, know Weniger. Beside managing the motel where he hooked up rooms for us, Tom is a central figure in the Mammoth skate scene and recently started a project called Mental Illness Orange (MIO) to bring skate communities together to turn off the phone and talk about mental health.

The parking lot the next morning was a melting pot of hype and good friends. Scott Blum pulled up first. Kimbel has known Blum for over 20 years through surfing, skating, snowboarding and everything else in between. He’s a renowned snowboarder known for everything from the steepest backcountry powder lines to lip-sliding 40-stair handrails. Blum was followed by Creature Skateboards Brand Manager Jake Smith and a few other friends tagging along from Yucca Valley, and we were all ready to hit Mammoth.

Volcon Brothers Skatepark in Mammoth takes days to study and learn. Sure, you might get in some grinds and maybe a line you think is tight in the moment on your first day, but to really make the park work it takes days of false starts, lightbulb moments, and building up your bravado to step to the 13-foot-plus transitions. The park doesn’t give out freebies, and you’d best believe you’re going to smoke at least one pair of pants during a session. And it’s all worth it. There’s really no other park on Earth that has a combination of organic flow, massive concrete walls and unique features quite like Mammoth. The park is also a reflection of its geography; instead of flattening the rocks, earth, and trees from the space, the builders poured the concrete around and onto the landscape that has resided there for millennia.

With the initial skate session being a success, we were all itching to unload the bikes and check out the endless trails surrounding us. We met Scott a ways outside of town at one of his local spots. It had rained earlier in the week, making the dirt soft and not too dusty, and Scott toured us around some singletrack trails he’s been saving in his back pocket for years. We were about 20 minutes out when we heard the first ping of hail bounce off our bikes, and soon we found ourselves laughing hysterically as we tried to find our way back in the onslaught of ice and cold. My iPhone was a casualty to the storm, but I’ll just chalk it up as one less distraction.

Our next camp area was nestled outside Mammoth in the surrounding Inyo National Forest. Scott clued us into the area, and it was far enough off the beaten path to provide the freedom we desired. Our camp sat in the middle of a large, wide berm with trees that could accommodate hammocks and provide shade during the long afternoons. Over the berm was a soft, sandy hill that dropped us onto miles of fire roads and singletrack.

Now that most of the skate footage was collected from the multiple, many-hour Mammoth park sessions, we turned our attention to ripping the bikes around the trails. One morning we even started connecting the dots between the bikes and skateboards with a bit of rope. A quick knot around the frame and a couple of ‘“hold my beer” jokes later, I found myself holding the line behind Jeremy’s bike waiting for the slack to kick. Turns out that getting towed behind a dirt bike on a dusty trail is just as fun and as dangerous as it sounds. It’s the soft dirt that will get you, but with some momentum and a little hubris, you can ride straight through the rocks and roots. The key to riding skateboard wheels on these dirt roads is to lean heavily on your back wheels and commit lightly to every turn. Having the crew there to fire you up with every careening turn doesn’t hurt, either. It was an epic ending to our time in Mammoth before we said goodbye to Scott.

Three hours south of the Oregon state line, my van sat idling at the summit of another high-desert pass as Jeremy shared tales of an empty pool in an abandoned trailer park that was victim to last year’s rampant wildfires across the state. Heading southwest, as opposed to our current northern route, would add another day to our two-week mission, but we all knew what could come of that detour. Skateable empty pools in the Northwest are scarce, and you have to wade through the rumors and fool’s gold to fine one that’s worthwhile. So, when Jeremy told us it was special, we knew it was a no-brainer to head south again to check the pit.

The pool sat in the middle of a scorched, flattened land, and we knew its days were numbered. There were no signs of the mobile park that was once here. The surrounding area was littered with construction equipment encroaching the pool’s edge, and within a couple of days they would sink their steel jaws into it. The capsule-shaped pool was really good — not just good for the Northwest, but good by any seasoned pool rider’s standards. The surface was fast with smooth transitions. The coping was flush with the tiles, and the death box and ladder were in the right spots. We caught grinds and lines until dusk fell on the scalded concrete.

Across the field from the pool, cars flew by to destinations unknown, and nobody paid any attention to the group of degenerate skateboarders hanging out in the bordering field. But if they did see us, they would have seen a group of best friends and a day we won’t soon forget. We go on trips like this seeking memories that we can preserve for the future, like the ones we captured at Mammoth Park or Ryes, or by getting towed down the dusty trails behind a dirt bike – where we missed the turn and wound up somewhere better – and the ones that leave us doubled over in laughter. Now that it’s all over, we know we can always find those moments, faded and folded in our back pockets, ready to revisit for years to come.

SOUTH AFRICA’S ROOIBOS HERITAGE ROUTE

Words and photography by Simon Pocock

The Cederberg mountain region of Western South Africa is home to the magical rooibos plant, and it’s the only place in the world where it can grow. The name rooibos translates to “red bush,” and the plant has been used by the Khoisan, or indigenous, people for over 300 years to create herbal teas with a number of health benefits and homeopathic medicines with reputable healing properties. Simple and subsistence farming has been the way of life in that region for hundreds of years, and to this day rooibos is still harvested by hand and processed by the people who live and work along the small tracts of land found in the remote mountains South Africa.

Feeling inspired to explore that unique history, we embarked on a motorcycle journey along the Rooibos Heritage Route, a road that winds north through the mountains from Wupperthal up to the arid plateau of Nieuwoudtville in the Northern Cape. This route connects sparsely populated villages and farms that still harvest the rooibos plant, and the overlapping mountains and deserts along the route are lined with stunning views of wildflowers as far as the eye can see. This lesser-known part of the world has an early frontier-like feeling to it, and the sight of donkey carts used to move between the small villages is common along the old trade route north. The region is packed full of history and beauty, and it made for an incredible experience to explore on two wheels.

Our plan for the ride was five days on the road, leaving from and returning to our homes in Cape Town. I was joined by two of my good mates: Dan Walsh and Paul Boshoff. We’re a small and nimble crew, all self-sufficient and capable of efficiently blasting across the desert and moving like the wind through the mountains. We would camp wild wherever the day drew to a close, and our goal was to keep the plan loose and allow the adventure to reveal itself with the passing landscape. We were on our own, in the middle of nowhere. Disconnected. No cell signal and nothing but open country and inspiring history ahead of us. It’s exactly the kind of escape we were looking for, and exactly where we wanted to be.

A MAD DASH TO THE EDGE OF AMERICA

Words by Ben Giese | Photography by John Ryan Hebert

Filmed & Edited by Kasen Schamaun | Produced & Directed by Ben Giese

The sky was dark and ominous above Grand Isle, Vermont, as my younger brother Mike and I geared up to head east across the old colonial backroads of New England. A bitter cold mist settled on the jet-black pavement as we layered up to stay warm for the rainy evening ahead. We had 72 fast and furious hours to slice through the neck of America, and 450 beautiful miles of lush rolling hills, charming historic towns and endless golden foliage ahead of us.

The plan was to zigzag our way to the great Atlantic coast of Maine, then turn south along the quiet shores of New Hampshire and Massachusetts to our final destination in Boston.

Within the first few miles we passed by some old farmhouses decorated with pumpkins and Halloween skeletons, and it was just the kind of October scene I had always imagined. I’ve dreamt of a motorcycle trip like this for many years now, and my long-lost fantasy to experience fall in the Northeast was finally happening. We were officially on our way, off into the autumn wonderland on two brand-new Royal Enfield Continental GTs, with all the miles ahead and all the things to see. I could hardly wait, and having my brother here with me just made the trip that much more special.

We’ve been riding together as long as I can remember, but we’ve never taken an adventure quite like this. And now that we’ve become adults living in different cities across this great big country, these opportunities and this time together feels a lot more meaningful.

Dusk began to creep in and the gray skies darkened as we passed through some dreary little East Coast towns. Dim lights illuminated the sleepy streets, and sad old homes with chipped paint were tucked away in the trees, hidden in the hills and forgotten to the world. These lonely towns radiate a kind of sadness, but not the depressing kind you might imagine. It’s more of a beautiful and poetic sadness, with a palpable sense of nostalgia that can only be found in these older parts of America.

Darkness came quickly and the freezing rain followed, so it was time to seek some food and shelter to warm our bones. We shivered into a cozy restaurant in an old brick building and laughed with joy at our newfound comfort, celebrating with a feast of smoked brisket and delicious local microbrews. Our shelter for the evening was just down the road in a cabin in the woods, where we lost our minds in a swirl of music, laughter and card games late into the night before falling asleep on a dusty couch to the soothing sound of rain on the old metal roof.

The dark clouds followed us that next morning, and we prepped for a cold and wet day ahead, but the gods of New England were kind and we managed to stay dry the entire ride. We were blown away by the beauty and charm of rural Vermont, so we took the longest way possible to Portland. We followed the backroads south, and then north, slowly creeping toward our destination in the east. We stopped frequently to take in the sights, but never for too long. We had to keep moving. There was too much to do, too much to see, too far to go, and we wanted it all. So we just kept going and stopping and going in a frenzy of excitement for the road ahead.

The hours melted away with the greenest rolling hills we’d ever seen, and we lost all sense of time and direction wandering the canopied forest as amber leaves rained down on us from the heavens. There were classic old trucks parked in front of big red barns, and little shops in small towns selling Vermont maple syrup. We were surely behind schedule to make Portland by dusk, but it didn’t really matter. There was a fairytale happening all around us, and we never wanted it to end.

New Hampshire blessed us with more beauty as the sun was getting low and pastel cotton candy clouds gleamed off the endless glassy lakes surrounding us. By this point, we started picking up the pace to make up for lost time, making it to the border of Maine just after dark. We crossed the entire state in blackness, like ships in the night through a daze of darkness and delusion.

I could see the lights of cottages flashing by in the woods, and I could smell fireplaces and cooking coming from inside. I imagined families at home, resting in their islands of comfort and warmth, with no sense of the crazed riders outside on a mad dash into the cold black abyss. Ghosts from the West, invisible to the world, sailing east through the haunted October trees of Maine.

We never saw the sun in Portland because our madness for the road ahead was pulling us forward to something more spectacular. And as we crested one final hill, the great Atlantic Ocean revealed itself, reflecting the deep-blue early-morning glow of a sun yet to rise. We made it to the end of the earth, 2,000 miles from home at the edge of the American continent, just in time to watch a new day begin. The world was still asleep as we stood on a cliff near the historic Portland Head Lighthouse. Waves crashed on the rocks below, and the sun slowly rose from behind the horizon, and all those crazy miles behind us were well worth the view.

It would be a much more mellow and relaxing day on the coast of Maine. We could finally shed some layers as the temps warmed up and a salty ocean breeze lulled us along the shore through dreamy beachside communities and quaint fishing villages. We made a few detours to check out some lighthouses along the way, and of course we had to try some lobster rolls for lunch, because that’s what you do in Maine.

When we finally reached the North Shore of Boston, we got tied up in the mania of rush hour traffic, with all the people coming and going, to and from the business of their lives. The defeated faces of Boston workers trying to get home on a Wednesday evening told the story of broken dreams and the search for cheese in a rat race that never ends. I felt badly for those people, and as the sun went down over the Massachusetts Bay, I contemplated how lucky we are to be here. To have this unforgettable experience with my brother, and to escape that mad way of living for a few days. And when I stop to think about the whole point of this whirlwind adventure, I realize there never really was one to begin with. It was simply about seeing a new place. Smelling it and tasting it and experiencing it for all that it is.

I used to sit and wonder what autumn in the Northeast might be like, but now I can dream about those rolling hills of Vermont and the wise old lighthouses on the coast of Maine. The trees and the farms, the glassy lakes and salty ocean breeze, the briskets and beers, and the sad towns and dark nights. I’ll remember all the little roads between, and all the things we saw along the way. Like ghosts of New England, invisible to the world, passing through for one moment and gone the next. Eyes fixed on the road ahead. The only road we’ve ever known.

A PLACE WHERE THE DREAMS NEVER END

Words by Chris Nelson | Photography by John Ryan Hebert

Filmed & Edited by Daniel Fickle | Soundtrack by John Ryan Hebert | Produced & Directed by Ben Giese

The dreams don’t end after we open our eyes. First, we taste the thick morning air that drips through the mesh of our tents, and in the tree branches above us we watch the tangled strings of pale green moss hanging down like long, bony fingers coaxing us to climb out of our sleeping bags. As we walk through the small, dank campground we see a thick brown slug slime its way up the side of an empty can of Rainier Beer, breathing through an open stoma on the side of its body. Then a deep voice cuts through the quiet dawn: “The water is warmer than the air is,” Noah Culver says as he stands knee-deep in Lake Quinault, which sits at the bottom of a glacial valley on the southwest corner of the Olympic Peninsula in Western Washington State.

Known as America’s last wilderness, the 3,600-square-mile Olympic Peninsula is home to rugged alpine mountain ranges, primordial beaches, salmon-filled rivers, and vast temperate rainforests that stretch from the Pacific Coast to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, which separates the northernmost edge of the U.S. from Canada. The Olympic Peninsula is now visited by over three million people annually, but native tribes had thrived in the formidably beautiful paradise for millennia prior to the arrival of European settlers in the 1500s, who came to poach otter pelts and strip the forest of its timber.

It wasn’t until 1897 that the area received its first national designation, Olympic Forest Reserve. Forty years after that, President Franklin Roosevelt visited the Peninsula and gave his support for the establishment of a national park in order to protect its natural resources, as well as the cultural histories of its Native peoples. Today, eight Olympic Peninsula tribes recognize a relationship to the park based on traditional land use and spiritual practices, and one of them, the Quinault Indian Nation, claims ownership of the water that Culver slowly wades through.

A Hollywood-based producer who has brought to life some of television’s most addictively and mindlessly entertaining shows, Culver shuffles his feet across the pebble lakebed with a steaming mug of instant coffee in hand. The ripples in the water break the still, mirror-like surface blanketed in an opaque layer of fog, split in the middle like an over-risen loaf of bread, and through the break we see the silhouettes of grand houses tucked into the trees on the far side of the lake, bathed in citrus sunrise. Suddenly another man, Mike Burke, bursts forth from his cheap, child-sized tent and runs into the water, until he trips and plunges down with a violent splash. When he stands up, he looks back at the shore with a wide, wild smile as water pours out from his snarled beard.

Burke owns a company that does large-format digital printing, and he and Culver were invited on this adventure by their friends Alan Mendenhall and Thom Hill of Iron & Resin, a Ventura, California-based clothing company. None of the four men had ever visited the Olympic Peninsula and thought it would be an idyllic location to ride motorcycles and photograph a lookbook for Iron & Resin’s newest collection. They invited META along to document their two-day ride north from the lake along the lone road that loops around the Peninsula, U.S. Route 101, to explore as much as possible before ending the trip at the top of Mount Olympus on the edge of the Peninsula’s largest city, Port Angeles.

Once everyone finishes their coffees, the guys saddle up on an eclectic collection of motorcycles: Burke has his Yamaha WR450, Culver rides a Honda XR600, Hill brought his Ducati Scrambler Desert Sled, and Mendenhall has a Harley-Davidson Sportster 1200 that he recently transformed into a Baja-worthy, scrambler-style bobber. They ride in a tight pack through the morning mist as small leaks of sunlight shimmer gold against their wet waxed-canvas jackets. After 30 minutes, they arrive at Kalaoch Campground, which is perched on rocky bluff above a sandy beach that is home to “The Tree of Life,” a large Sitka spruce tree that continues to green despite the ground around its roots having eroded long ago, making the tree appear to float in the air.

We set up camp at a first-come, first-served site before getting back behind the handlebars and riding an hour inland to the Hoh Rainforest, one of four temperate rainforests on the Olympic Peninsula. We wade through the mile-long Hall of Mosses trail loop, which can be one of the quietest places in America. We stare up at the lush green canopy created by the huge, knotted branches of big-leaf maples, cedars, spruces, hemlocks, and firs, with bright-yellow leaves falling through beards of clubmoss and swaying epiphytes. Underfoot is a soft, soggy forest floor of mosses, lichens, and ferns that Burke can’t help but jump up and down on, amazed by its sponginess. Culver quips that it looks like the Hobbit home of the Shire, and asks, “Did anybody else’s feet just grow a few inches, or is it just me?”

On the way back to camp, we decide to stop at Ruby Beach, where massive sea stacks stand sentry just offshore, bald eagles nest in the bluff trees, plum starfish crawl through the coastline tide pools, and huge piles of driftwood collect on the shingly beach, the bones of the rainforest picked clean by the sea. Burke jumps up onto a long-dead tree trunk and starts pushing his feet forward, riding the driftwood down the beach like a professional log roller.

He loses his footing just before reaching the water, but then out of nowhere, Mendenhall jumps on and finishes the job. Unfortunately, the fun was short-lived, because Instagram fame turned this once-untouched beach into a destination for van-life influencers and misguided couples who force their camera-shy dogs into self-indulgent engagement photos, and before long our patience wore thin, our bellies moaning for dinner and beer.

Back at camp, Willie Nelson plays through a Bluetooth speaker as we build a campfire and watch Hill plop sausages into a beer-filled crock, cutting potatoes into wedges and wrapping them in aluminum foil lined with butter and garlic. For whatever reason, food is more satisfying when cooked over an open flame. We spend the rest of the evening sharing stories, telling jokes, and laughing under the moonlight.

The forecast had called for heavy rain throughout the night and into the following day. Most of the Olympic Peninsula is typically wet and rainy, especially in the shoulder seasons and winter, so we had figured it would likely be unavoidable. As we head north the following morning on the 101 through the now-famous town of Forks – where Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight book series is based – the gloomy scene still feels like a dream, but one that at any moment could turn into a nightmare: darker, drearier, more ominous and foreboding, yet still undeniably captivating. Thankfully we get to enjoy a short break in the weather as we ride around Lake Crescent, a deep, glacially carved lake in the northern foothills of the Olympic mountains.

The rain falls in cold, whipping sheets as we start up Hurricane Ridge Road, a steep, 17-mile stretch of smooth pavement with tunnels, chicanes, and long corners that climbs to an elevation of over 5,200 feet. On a clear day the peak offers incredible panoramic views of Olympic National Park, but all we can see are dark silhouettes of pines set against the faint outlines of distant mountaintops. All four guys tremble with cold in the dripping wet, but they can’t help but smile. Burke says, “It’s about enjoying these moments, no matter what. Even riding through this pissing rain, I don’t care that my legs are cold, and my hands are frozen ... it’s clarity, it’s freedom, it makes me feel alive and brings value to my life.”

We all crack open beers and offer cheers to the Olympic Peninsula, which we agreed is one of the most fantastically inspiring places any of us has visited. Though it is no longer untouched by modernity, the Olympic Peninsula remains a sanctuary for those seeking asylum from the pressures of contemporary living, and its wiles are best experienced from the seat of a motorcycle.

Culver puts it best: “We live in this world full of complication, where you’re constantly having to choose your words carefully and negotiate this crazy world we live in, but anytime you get out into a place like this, it’s full of honesty. If it’s cold, you’re cold. What you see is what you get, and there’s no complication to it. You get to be in this situation where all of those complications are gone, and as humans we crave that kind of honesty.”

As much as we want to descend into the town of Port Angeles and find somewhere to warm our bones, none of us moves an inch, unaccepting of the impending return to normality and life’s complications. We let the rain slap against our skin as we search through the darkened trees to find grazing blacktail deer and squint to find the massive blue glacier at the peak of Mount Olympus, and in that moment, we shared the significance of standing in one of the most awe-inspiring places in America. We never would have been able to leave if we didn’t believe that when we lay down in our beds that night, the dream would continue even after we closed our eyes.

VOLUME TWENTY-FOUR

Words by Ben Giese | Photo by John Ryan Hebert

Lately, my eyes have been buried behind old books, fixed on the compelling words of the great Jack Kerouac as they effortlessly spill out onto the page with colorful texture and a refreshing lack of regard for the rules. He says things in strange ways, combining random words and nonsensical punctuation, but somehow it all works beautifully. He does it all wrong, and that’s what makes it so right.

We’ve never really been interested in following the rules, either. And we’re not all that interested in doing things the way they’re supposed to be done. That’s why we started a print publication at a time when the world was going digital, and it’s why we chose to pursue real-world experiences and create a tangible product when the rest of the world was moving online. It’s why we tell these stories about such unique people and places, and work with photographers and writers who choose to see the world through a different lens.

Kerouac’s voice was a rejection of things like authority and materialism in favor of virtues like freedom, rebellion and fearless individualism – the same virtues we founded META on over eight years ago. We value our individuality above all else, so when the news broke that a corporate Goliath was changing its name to Meta, it felt like a punch to the gut. With the flip of a switch our identity was suddenly watered down, and we watched our name circle the drain and wash away with something we had no control over.

Cover photo by Tyler Ravelle

But our brand is much more than just a name. We represent a way of living. We speak to inspire and encourage the rare breed of humans out there bold enough to chase their dreams and never look back. The ones who live with passion and enthusiasm and share an obsession with all things fast and fun. I think Kerouac said it best:

“The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles...”

That fire is still burning inside of us, and the death of our name isn’t going to prevent us from keeping this dream alive. We will continue to publish this magazine and create the same content you’ve grown to know and love, but this will be our final issue with the title META. We’ve embraced this moment of change as an exciting opportunity to revitalize the brand, rethink our approach and further improve on the work we love so much. It’s blessed us with a fresh outlook and a jolt of renewed creative energy we can use to burn and crackle with excitement for what’s next. The future is glimmering gold, and the possibilities for the road ahead are endless, so like Kerouac says, “just keep on rolling under the stars.”

A Story by Prism Supply

"These days, most people wouldn’t think twice if a black man were to ride a brand new Harley-Davidson passed them on the street. But, back in the 1940s and ’50s when Tyree “Tye” Smith helped start The Mohawk Delegation - that wasn’t the case,” Mark Smith, Tye’s son, explained as he shared his dad’s story.

Tye grew up in Nashville, but moved to Indianapolis as a young man where he made a living as an auto mechanic. While wrenching on cars was his day job, his passion was undoubtedly motorcycles. “Dad grew up riding motorcycles with his father and brother, my uncle Claude. In fact, most of his brothers were involved with motorcycles in some way. And, for them, the ultimate motorcycle to own was a Harley-Davidson,” Mark explained.

This was the height of the Civil Rights movement and there’s no question our country was working through serious racial conflict. As black men in mid-century America, it wasn’t culturally acceptable for Tye or his brothers to walk into a Harley-Davidson dealership and ride away with a new motorcycle.

Mark describes his dad, who always had friends around, as very loving. People would travel from all over the midwest to spend time with Tye and his group of friends as they attended motorcycle field meets and various other events.

So, in the early ’50s, thanks in part to his warm personality, Tye was able to forge a friendship with the owner of Southside Harley-Davidson in Indy who dismissed the cultural standard of the time and decided to sell a brand new 1952 Harley-Davidson Panhead to Tye.

Finally, with a brand new Harley of his own, Tye started to add his own flair to it - like most of the things he owned. Two weeks into owning the motorcycle, Tye stripped the bike down and sent everything to chrome. “It was one of the only completely chrome motorcycles in that area,” Mark explained as he described his dad’s Panhead. The Panhead was soon named Dreamboat and Tye continued making it his own by way of a custom seat (with his name on it) and a fully-custom continental kit on the rear among many, many other modifications.

One of the most unique features on the bike was a little Native American figure on the front fender which signified that Tye was a member of The Mohawk Delegation, an Indianapolis-based African American motorcycle club he helped start. Tye, alongside members of the delegation, proudly rode around town and throughout the country - enjoying the motorcycles with like-minded individuals.

However, “It was tense at times,” Mark told us as he recounted old stories of his dad’s motorcycle trips. You can imagine the sort of racial tension 50+ African American motorcycle riders caused when they passed through town or pulled into gas stations, many of which would not serve them because of their skin color.

Nevertheless, they persisted. They fought against the cultural standard by simply enjoying their life. Frequent family cookouts at the house and motorcycle events filled their weekends. Looking back, Mark explained, the more The Mohawk Delegation (and other groups like them) were seen around town and throughout the country on their bikes, the more it helped to normalize the perception. Over time, the sight of a black man riding a motorcycle down the street became more and more common.

In the ’70s, Tye’s health began to decline and he slowly stopped riding his motorcycle to gatherings. “He would still trailer the motorcycle to the events even if he couldn’t ride it, “ Mark remembered, “People expected to see that bike - Tye and Dreamboat were fixtures in the community.”

In 1980, Allen Tyree Smith passed away, leaving a lasting mark on the motorcycle community and the world around him and leaving Dreamboat to his family. Soon after, Mark brought the bike to his mother’s house where it sat covered and untouched for over 40 years until 2020 when Mark’s mother passed. Mark was tasked, once again, to recover the motorcycle and had to decide what its next chapter would be.

The motorcycle is a time capsule from 1952 and represents an era when black motorcycle enthusiasts were publicly shunned and chastised for owning and riding motorcycles. But, more importantly, Dreamboat represents a man, Tye Smith, from Indianapolis who decided not to conform to his culture’s rules. Tye went full speed against the grain of what was generally accepted and helped a generation of black Americans to claim their position as equals during a time when many of their neighbors didn’t believe they had the right.

So, instead of parking Dreamboat under a cover in his garage, Mark decided it was time for the world to hear the story of his father and his motorcycle in hopes that today’s society would benefit from the story of Tye Smith and Dreamboat.

So, he contacted us after learning about our recent mechanical restoration of Bronco Bronze, a 1952 Panhead found in Charlotte with a storied past of its own. The Prism team got Dreamboat running and riding again after all those years of sitting. Mark and his cousin, Earl (former Rough Rider’s President for 30+ years), even had the opportunity to visit Charlotte where Mark got to ride his dad’s bike for the first time since his father’s passing in 1980.

Although parting with that bike was one of the hardest decisions of Mark’s life, he tells us, “I think dad would be proud. What's coming out of this is more important than the sport of motorcycle riding itself. The fact that he was one of the first black men to stand up against what was culturally unacceptable at the time.” Mark continued, “Other people can learn from his story. If you believe in something and stand up for yourself, you can help right a wrong if you stand up for injustice - whether that be because of sex, race or whatever - believe in yourself.”

A story by Triumph | Photography by Kevin Pak of British Customs

Inspired by his love for adventure, and the great outdoors, John Ryan Hebert is an automotive and lifestyle photographer based in Los Angeles. Exploring the state of Southern California on two-wheels is a constant source of inspiration for John, and the number of miles he has clocked up is reflected in the beauty of his work.

Building on the premise of the modern classic custom culture in LA, John tells the tale of his beloved 100,000 mile Bonneville and its multiple guises as a café racer, scrambler and desert sled to name a few.

‘For a long time, I’ve had an affinity for British design DNA’ Says John. ‘Some uniquely fantastic cars and motorcycles have come out of there, even the music scene always resonated with me. The Bonneville has such a classic look - simple and elegant. It’s a shape that will never go out of style.’

‘When I originally bought my Bonneville, I wasn’t intending on customising it too much as I thought it already looked great! I used to go down to the garage at night and just look at it sometimes, ogling.’

‘Not only did the bike have style, I also needed it to be super reliable as it was my sole mode of transportation. I used to commute over 100 kilometers a day to and from work, rain or shine. I needed something that was an extension of myself, something I could live with daily and wouldn’t break down or give me any hassle. The Bonneville fits the bill.’

We asked John what inspired him to take the plunge and customise his Bonneville, here’s what he said:

‘I was first drawn to the café racer culture when I was canyon riding. A lot of people just think of the ocean and Venice Beach when they think of Southern California, but the topography of the region is rugged which makes for some incredible riding. The roads snake through deep passes and over tall ridgelines. You can spend an entire day in the Santa Monica mountains or Angeles National Forest without hitting a single stretch of straight road. It’s a place where you can lose yourself and be fully immersed in the ride.’

‘I installed clubman-style handlebars on the bike, which created the illusion of clip-ons. This pulls your body forward connecting you to the curves of the road. Adding a café racer style seat completed the look, throwing it back to the vintage TT race bikes of the 60’s that raced on the Isle of Man.

‘After a few years of riding, I started taking the bike further on longer, more frequent rides. Exploring new territory, the desert became my source of inspiration. I really liked the feeling of being small, and seemingly engulfed by the vast endless landscape.’

‘Being out there made me look around. I was always seeing roads and trails that went off into the abyss, wondering what hidden treasures they held. This intrigue led me to start thinking about converting the bike into a scrambler-style Bonneville. I worked with Kevin Stanley at Moto Chop Shop in LA who essentially made my dream a reality, giving me the tools to take my adventures further. We switched out the café racer seat for a flat bench style seat, throwing some moto bars on and giving the bike some knobblytyres - minimal effort and budget required. Seeing the bike in that style reignited my passion. It felt like I had just bought a new motorcycle! Changing some simple components really unlocked a whole world that I didn’t have access to before.’

‘After the scrambler came the flat tracker… I was introduced to racing through my friend Jordan Graham who races in National Hare & Hounds. I was really into desert-riding and he pushed me to join the Hooligan class, which is an NHAA racing class of bikes 750cc and up. Hanging out at a few races with Jordan and experiencing the community vibe really pushed me to take the plunge and dive into the world of racing. The community aspect of racing reminded me of going out to play pool in a league with your friends, just a little more gnarly.’

The Bonnie’s first race was the Biltwell 100, the perfect entry point to desert racing. We didn’t do a whole lot to the bike; we wanted to try and keep it as authentic as possible. We took the airbox out and gave it pod filters to let it breathe as freely as possible. We also fastened a set of Predator Pro pipes to increase power output. For ergonomics and handling, we put on a set of Mule tracker handlebars with some risers. The rear shocks were custom-built for desert racing. After the Biltwell 100, we set off for Nevada to race the Pioche GP. This one was way more technical. Finishing that race was one of the most challenging things I’ve done both on and off a motorcycle. A podium position was the cherry on top.’

After covering over 100,000 miles on his Bonnie, John tells us which were the most memorable and why:

‘The first few miles I took on the freeway the weekend I bought the bike will always have a special place in my heart. Having a machine that could cruise at speed comfortably on the open road was a novelty to me and something that I relished.’

‘My most memorable trip though must be travelling across the continent in 2020 to visit my family. It was an honour to experience the journey in such an intimate way. In a car, everything goes by in a blur. You’re not really connected to the world around you and you can travel hundreds of kilometres in a daze. It’s so much more immersive on a bike, stopping every 150-200km for fuel in random towns, camping out between rides. It really is something special.’

‘Owning a Triumph Bonneville really is just an extension of yourself, in a way. You can make educated inferences about somebody just by looking at their bike. Mine is covered in dings and scratches after covering so many miles, and if you swipe a finger across the tank or seat, you’ll find out that it’s actually black under there. But that’s why we ride. For the freedom, for the fun and for the experiences.’

‘The Bonneville stands for simplicity and adaptability, which I think are two important components of life. A true Bonneville also symbolises timelessness and avoidance of trends and quick fads that are here today and gone tomorrow.

The Bonneville will always look good and will always be relevant no matter what form it takes.’

Words by Andrew Campo & Dale Spangler

Photography courtesy Dunlop

The road to professional motocross starts at an early age. National amateur champion titles start in the 51cc four to six-year-old age bracket every year at Loretta Lynn’s AMA Amateur National Motocross in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee. It’s a long, difficult journey through the amateur years that thousands of young racers and their families dedicate their lives to chasing. Not many move on to compete at the professional level, and only a handful of racers ever achieve their goal of standing atop the podium. Even fewer etch their name into the history books as a class champion.

On June 21, 2020, Eli Tomac cemented his legacy as an elite champion, becoming only the fifth rider in history to win titles in both the 450SX and 250SX classes in Monster Energy Supercross and both 450cc and 250cc classes in AMA Pro Motocross.

That day, Dunlop’s Senior VP of Sales and Marketing, Mike Buckley, was overcome with emotion as he reflected back to 2007, when he had set in motion a developmental amateur motocross program focused on supporting a select group of championship-level racers as they make their way through the amateur ranks and aspire to become future AMA Motocross and Supercross champions. Tomac was among the first group of racers chosen for the program, and Buckley had just witnessed his vision come to fruition at the pinnacle of the sport through Tomac’s incredible journey.

It had all begun as an idea in 2004, when Buckley built a practice track for his kids on his property in Western New York, which quickly turned into racing motocross as a family at the local level. As Buckley learned the ropes of amateur motocross, he noticed that racers at the local level idolized regional pros and upcoming amateurs as much as they did the national-level pros. For Buckley, it was a lightbulb moment:They already were supporting an elite group of professional motocross racers, so why not do the same for amateurs? An elite amateur support program was a way to further validate an already successful rider support program while building upon its philosophy to continually help nurture and grow the sport of motocross.

Some years later, in April 2007, Buckley rolled out the new amateur rider support program, dubbed Team Dunlop Elite. The program’s goal was to identify outstanding young minibike racers and provide them with the support and guidance needed to navigate their amateur careers, with the ultimate goal of one day racing at the professional level. The team made its official debut at the World Mini Grand Prix in Las Vegas that year, composed of 17 elite, upcoming young racers handpicked to represent the program for their potential to be the next Motocross or Supercross superstar.

In 2008, they moved their elite team launch to Texas for the annual Lake Whitney Spring Amateur National, where 18 amateur racers were introduced to represent the brand. Since then, the event has become an annual occurrence, and each year elite team riders are invited to Texas for the official launch. Riders and parents are educated about the program’s benefits; each rider receives exclusive team apparel; and a special guest speaker is chosen to address the gathering. The entire experience is designed to welcome riders and their families to the team through an inclusive one-of-a-kind experience.

Support at the amateur level is earned and often hard to come by, and the overall cost of racing is an enormous investment. All too often, money is a deciding factor when a family is forced to throw in the towel, which is why the program is such an invaluable tool for those who make the cut. It’s become an integral part of the path to professional motocross success.

In 2013, as the amateur racing scene continued to evolve, Buckley hired Rob Fox to take over and administer the program. At the time, Fox worked for Florida-based Nihilo Concepts, a brand with a consistent presence at amateur national motocross events. Buckley knew he’d found the right person to take ownership of the program and take it to a new level. For Fox, it was a dream come true: traveling to races and working with riders and their families at the helm of an elite amateur rider support program for a legendary brand. As the newly appointed Amateur Motocross Support Manager, Fox quickly set to work adding to the program’s foundation by focusing on small details that make a difference—like the personal message he sends to each team rider before an amateur national that includes his recommended tire choice and air pressure for that racetrack. It’s something no other tire brand does, especially for amateur minibike riders.

For Fox, the connections he’s made with racers and families, along with seeing top amateurs grow as riders and individuals, are some of the best parts of his job. He considers his riders and parents a part of the Dunlop family and a part of his own family. Likewise, riders and parents feel the same: “To be part of the team is an accomplishment, and there are no words to depict what it means to represent such an iconic brand that our family loves,” explains Shawna Steinbrecher, mother of minibike phenom Eidan Steinbrecher. “Everyone involved on the team is first class. We will forever cherish the memories made while being on the team.”

Lisa DiFrancesco, the mother of program alumnus Ryder DiFrancesco, feels similarly, “Over the past ten years, we have been fortunate to be the longest-running athlete in the program,” she explains. “Ryder’s success over the past ten years has a lot to do with the people and products that support him. We can’t thank them enough for all they have done—on and off the track—to support Ryder.”

“The program is the original and quintessential ‘Elite’ team in amateur motocross and has the history to prove it,” explains Harold Martin of MotoPlayground. “What started as Mike Buckley’s vision in 2007 has proved to guide and shape the pathway for so many professional racers today.”

For 2021, the team is composed of riders Haiden Deegan, Drew Adams, Casey Cochran, Seth Dennis, Ryder Ellis, Kade Johnson, Eidan Steinbrecher, and Kyleigh Stallings. This year’s team was introduced in conjunction with the Spring A Ding Ding event in Texas, with Mike Forkner, father of program alumnus Austin Forker, as the guest speaker.

One would think Buckley had a crystal ball back in 2004 when he realized top-level amateur riders are often the local heroes in any given area. For 15 years, the program has fostered championship level racers and helped support 90 riders as they chased their dreams of becoming a professional. Graduates of the program that have gone on to successful pro careers include Eli Tomac, Justin Barcia, Chase Sexton, Adam Cianciarulo and many of the other current top-level professionals. A veritable who’s who in the current professional Motocross and Supercross ranks, and something that has earned Dunlop a place in the history books by creating one of the most effective and influential rider support programs.

“It was definitely an honor to be selected as one of the inaugural team members back in 2007,” Tomac shares. “Looking back at how many top riders have graduated from the program and made it to the Monster Energy Supercross and Lucas Oil Pro Motocross series is pretty amazing. Most of my main competition at each race were once members. It’s nice to be part of that fraternity.”

Words by Steve Shannon

Photography by Lindsay Donovan & Steve Shannon

The Columbia River is one of the most dammed rivers in the world. From its headwaters near the Rocky Mountains in British Columbia, nearly all of its 1,243 miles are now controlled by a series of 14 dams. In Canada, these dams and reservoirs are used for water storage, to control flooding and store water for downstream power generation. This results in wildly fluctuating reservoir levels, up to 150 vertical feet. At the peak, these reservoirs create beautiful lakes, but as the water supply is used over the winter to heat the Pacific Northwest through hydroelectricity, the reservoirs are slowly drained to completely empty by spring.

It’s during these early spring months that a brief opportunity exists to explore these reservoirs. A once-lush landscape full of flourishing old-growth forest and productive farmland, now reduced to a barren, desolate wasteland. Stumps, old buildings and roads, and an array of unique patterns and textures offer a glimpse into a habitat that has been erased in the name of cheap electricity.

But what is the actual cost of that power? Just three of these Canadian reservoirs cover nearly a quarter-million acres. We’ve cut down entire forests that will never regrow to their former splendor. We’ve destroyed fisheries and pushed several species to the brink of extinction. I hope these photos will not only inspire people to get out and ride, but to think about how we can continue to move toward a future in greater alignment with nature.

Words by Forrest Minchinton | Photography by Monti Smith and Will Luna

We all know the Hawaiian Islands are an amazing vacation destination. A glorious place boasting beautiful beaches, picturesque valleys, and more than its fair share of unreal natural beauty. Filled with resorts of all kinds, golf courses a plenty and rife with all manner of opportunities for leisure. An archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, numerous smaller islets and seamounts loosely gathered together and plonked smack bang in the middle of the North Pacific Ocean.

It all came about from an out of the blue call to go race our 40+ year-old dirt bikes at the 68th Annual Garden Isle Grand Prix on the island of Kauai, and it was one of those calls where we have no other choice but to just say yes and figure out the logistics later. We raced, we laughed, we made new friends, and we drank more than a few cold ones. Aloha and stoke was shared by all and we all walked away with one hell of a good memory in the bank.

Words and photography by Max Marty

I never really knew my neighbors here in Kila, Montana, until recently, when I met Logan Vaughn. Logan and I went to the same high school, but we only officially met this year and have become fast friends ever since. Logan enjoys working with his hands, and he is currently building a log cabin and fixing up an old sailboat. I’m a photographer by trade, but I also enjoy building things, too, so together we took a job in Oregon outfitting out a custom Ford Transit van for a local company. It would be a fun job with my new friend, but we had no idea that our time spent out there would spark the idea for a return on two wheels, and an unforgettable adventure that would ensue from our homes in Montana to the Oregon coast and back.

On that job in early April, Logan and I were driving one loamy dirt road after another. The roads angled up and away through misty forests of impossibly tall cedar trees. There were winding creeks with bordering hot springs and patches of ferns and moss so thick you just had to lie in them. It felt like a motorcycle adventurer’s paradise, but unfortunately, we were on a job with a tight schedule and confined to the cockpit of the Transit van.

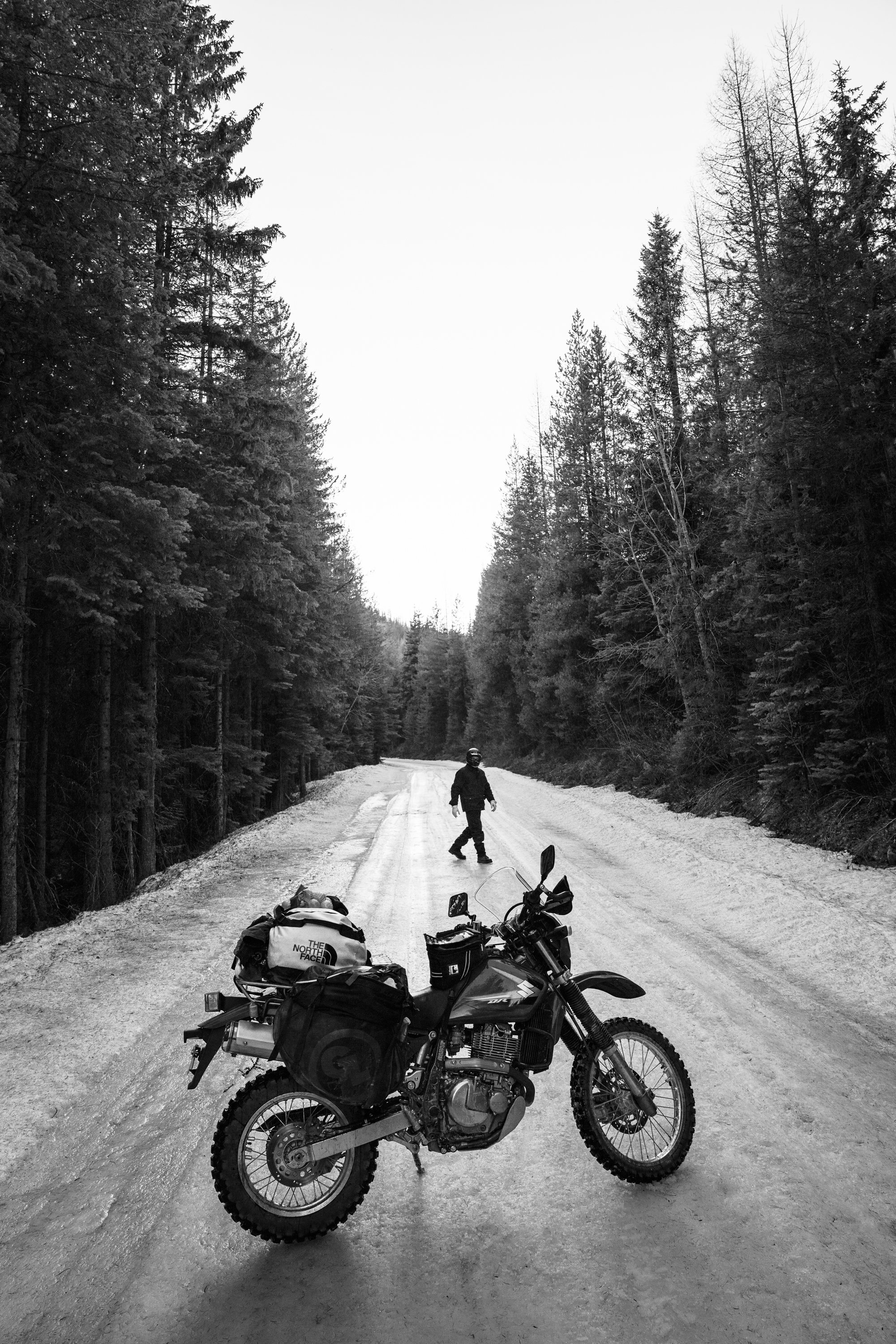

For two young, Montana-raised boys, it was humorous to be in such a beautiful new environment, surrounded by the inspiring wilderness and trapped behind a windshield like wild animals in a cage. It wasn’t right, and we wanted to make it so. We both turned 21 this year, and together we decided that we would celebrate by making a return on motorcycles, taking mostly dirt roads to get there. The following week we returned home, made our plans, prepped our DR650s and hit the road a few days later.

The first stretch of the trip was a brutal affair. My bike was slowly rattling apart, and as I replaced the countless nuts and bolts one by one, it began to feel like I might do a complete rebuild using Ace Hardware parts from various small towns. Then my 70-200 camera lens fell off my bike, over a cliff, and down 75 feet into the Koocanusa Reservoir in Montana. I was being taken to the cleaners.

Much of the roads in Montana were still covered in ice and mud. Riding was slow and tedious, and this was starting to feel less like a celebration and more like some sort of punishment. We averaged 60 to 90 miles per day, and almost every dirt road we took led us through snow so deep you couldn’t see the wheels of the bikes. We were feeling worn and weary, and setting up and taking down camp was a brutal affair because the weather was poor most nights. We rarely had any idea of where or when we’d camp, and finding old wooden sheds or decommissioned fire lookouts became the norm.

There was one night that stood out in particular, in Northern Washington, when we decided to ride up to a fire lookout that we saw off in the distance. Shortly after taking a ferry across the Columbia River, we started gaining elevation, and with every switchback the road began to disappear under a blanket of deeper and deeper snow. This time, though, it became so deep that the road was impassable on our bikes. Logan’s theory was to take a downed tree and lay the most flat and uniform section on the snow to ride over it, then repeat until we reached our shelter. Although bizarre, it made sense, and it worked. Lewis and Clark would have been proud. Inch by inch we finally made it to shelter, crawled into bed and slept for two days.

Often during this trip, in the later hours of the day, our dwindling appreciation for these moments would spill out and paint a picture of excitement for life. A strange feeling of thankfulness for the long and tiring days on the road and the feeling of accomplishment after getting through it. It is so refreshing to escape the rat race and reset, if only for a moment. And to do it all with my new friend and neighbor, Logan.

We made it to the Oregon coast on day ten with the town of Seaside harboring our finish line. Logan and I sat quietly on a cliff, eating sandwiches and watching the sun set over the Pacific. We shared eagerness for the next day, and went so far as the next year. We slept underneath a picnic table that night as it rained, and I laid there reminiscing on what an unforgettable ride it had been, wishing it didn’t have to end. And that’s when it struck me. We still had to ride back to Montana. Another ten days.

Words by Matty Chessor | Photography by Steve Shannon

The darkness of midwinter gloom and a failing relationship fueled the planning. But what started out as a distraction wound up becoming an unforgettable dream adventure north to the Yukon. My good friend and talented photographer Steve Shannon and I would be riding dual sports with hard seats, no fairings, and knobby tires. It wouldn’t be comfortable or glamorous, but it would no doubt be glorious.

From our homes in the Kootenays, British Columbia, we trucked our bikes 700 miles northwest to the small town of Smithers. From there we would unload the bikes and leave the truck behind, beginning a mostly dirt route that would guide us from British Columbia through the Yukon, into the Northwest Territories and over to Southeast Alaska, returning down the Inside Passage on the state-of-the-art 1960s Alaska ferry fleet. Our plans were loose, our gear was tight, and we had three weeks to burn before our ferry date. This is the highlight reel.

Unfortunately, our first leg of the trip on the once-dirt Stewart-Cassiar Highway had now been sealed in asphalt, but the awe of the surrounding wilderness and amazing scenery remained, and the challenges that inevitably come with any motorcycle adventure would ensue regardless. We quickly encountered our first flat tire around Meziadin Junction. A small speed bump to start off with on day one, but the payoff would come from the next 40-plus miles riding west through the jagged mountains and glaciers into the small town of Stewart.

Stewart is the southernmost access point into Alaska and is rich in exploration history — an outpost for early pioneers and modern two-wheeled explorers like us before leaving the pavement behind and venturing farther into the Great White North. Pack some provisions, fuel up the bikes, and spare your first-born here because it only gets tougher the farther north you go.

A few hours later we found ourselves riding above the spectacular Salmon Glacier, and the breathtaking views left me thinking I was back living on the West Coast of New Zealand. We were on an old mining road that was perched up 300 meters, with the powerful glacier slicing through the valley below. Life was good in these moments, and these were exactly the types of experiences we had desired all winter.

The following day we made it to the small village of Dease Lake, where we scooped up a few six-packs that balanced on the seats between our legs and some Chinese takeout that flapped around in plastic bags hanging from our handlebars. We found a nice campsite by the water and enjoyed a few cold ones and an everlasting sunset on a perfectly still night. The haunting call of loons echoed across the water, and the sunset was perfect. It was 11 p.m. In a fleeting moment, Steve thought he would miss the sunset shot and called out for another camera lens with haste. The quickest way there was the KTM, barking back at the loons to the water’s edge. From that moment on the old girl has been affectionately named The Loon.

Farther north we finally crossed the border into Yukon and onto the Canol Road. The Canol project was both an engineering masterpiece and a blunder by the U.S. army during World War II. Built to provide a secure oil supply to Alaska, the Canol project throttled crude oil through a 4-inch pipe over 600 miles, from the town of Norman Wells through Ross River and Johnson’s Crossing into the refinery in Whitehorse. It operated for only about 14 months before being abandoned, and the harsh environment has since eroded the unmaintained bridges across major rivers, making the route nearly impassable. What’s left is a beautiful, unpopulated land, tarnished only by the remnants of past oil and mining projects left to rust when the markets declined. Nature has slowly reclaimed the land, and the porcupines are delighted, left to chew on the tattered remains of abandoned shelters.

The southern stretch of Canol Road is well maintained and made for some excellent riding surrounded by broad valleys, frigid lakes, expansive vistas, and copious old mining routes to explore. By this point of the journey, our spirits were high, but we realized our fuel was running low. We had to turn the engines off and coast downhill, slowly lugging the bikes uphill, valley after valley trying to sip as little fuel as possible, eventually rolling into Ross River on fumes.

The small, unincorporated community of Ross River sits on the banks of the Pelly River, with access to the North Canol across a cable-driven ferry. Unfortunately, we showed up five minutes late, and we learned the hard way that ferry service ends strictly at 5 p.m. So, we settled in for the evening with some warm hospitality from the locals and camped out on the banks of the Pelly River until we could cross in the morning.

The farther you go into the wilderness, away from civilization, the stranger the encounters with other humans seem to become. After 50 rough miles up the North Canol Road, we stumbled onto a scene that only Quentin Tarantino could conjure up: a man standing there in the road, next to his two-wheel-drive Rokon with a sidecar, German-style army helmet on, dressed in all black, pump-action shotgun in hand, glaring us down as we rode toward him. What do we do? After stopping for a chat, we ended up talking with him for a couple of hours. He said his name was Winter, a fitting name for a man living out here in the wild and frigid North. He lives a reclusive life out here and told us about the secluded camp he had built — his own version of paradise, hidden in what we affectionately deemed the “true middle of nowhere.”

When we crossed the border into the Northwest Territories, the roads quickly degraded into rough tracks, and we were now well past the point of any maintained roads. It began to feel more and more desolate, and more and more dangerous. We pushed on until a moment of reckoning, when we eventually arrived at a snow-covered river crossing 170 miles from the nearest sign of civilization. We decided to spare our lives and call it, so we turned around and started heading back south, eventually stumbling on Winter’s hidden camp. We waited there for a few hours until our ears perked up to the sound of his Rokon bumbling up the trail at midnight. It was the summer solstice a few degrees south of the Arctic Circle, and we all watched the endless sunset dance across the peaks around us. We swapped stories around the campfire, and the sun melted into sunrise without ever dipping below the horizon. Low on sleep but high on life, we packed up and made our way west toward Alaska.

The Top of the World Highway west of Dawson City, Yukon, is a little over 65 miles of dirt road following scenic ridgelines that lead to the Alaskan border. After a thorough interrogation by the border patrol, we were reluctantly let into the US of A, and the beautiful smooth tarmac felt like one hell of a greeting. It was a short-lived 7 miles of relaxation before an abrupt change back to the potholed dirt roads we had become accustomed to. We continued down the winding road into the port town of Skagway, Alaska, where we would catch our scheduled boat back to the south.

Alaska ferries run like a broken Swiss watch, with aging vessels and a care for time not felt back home. Motorcycles below, a bag of wine on the sundeck, the next few days melted away with bliss. With over 3,200 miles of seat time already, this downtime was a welcome break. We stopped at several stations on the way down, and even got off to explore at some of them.

Sitka and Juneau were both beautiful stops that granted us some limited but fun time for exploring. It was the Fourth of July in Juneau, Alaska’s capital, and it was an American cultural experience I was not expecting. We rode off the ferry in style, illuminated by a fireworks show that lasted a full 8 hours in the sky above. Then, at the seaside town of Sitka, we quickly explored the limited road network (all 14 miles of it) and took another small boat to neighboring Kruzof Island, home to Mount Edgecumbe, a dormant volcano. With our limited time, we blasted around some trails and rode up to the rim of the cinder cone. We then played around on a deserted beach before catching the return boat to Sitka.

Upon arrival at our final stop in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, just as the sun set, we quickly navigated one final border crossing before one last fleeting ride into the fading daylight. After three weeks of never-ending light, it was a surreal feeling to watch darkness enshroud the land. Or maybe that was just the dim joke of my 2006 KTM headlight. During one final night camping along the shores of the Skeena River, we listened to the crickets chirping as the river gurgled us into a short-lived sleep.

No matter where life takes us from here, this was an adventure that Steve and I will never forget. It’s a time that will live on forever indie of us, to look back on with fondness and fuel more adventures to come. We both feel so lucky to be alive in this moment, and as we arrived back at the truck in the early morning, the abrupt end to the trip was a shock to my system. Just like that, it was all over, and on that long drive home I just kept wondering if it was all a dream.

Words by Ben Giese | Photography by Jimmy Bowron

The story of life on Earth is almost as old as Earth itself, spanning across time horizons so vast the human brain can hardly fathom it. For the first billion or so years, the planet was a fiery hellscape of searing ash and molten rock. Lightning electrified the skies in thundering chaos as asteroids rained down from the heavens. Volcanic eruptions were frequent and violent, spewing gasses and water vapor from the mantle up into the atmosphere. Those gasses would help produce our oxygen-rich environment, and that water vapor would eventually cool and condense to form our oceans: a primordial soup rich in carbon-based chemicals that would give birth to the first forms of life over 3.6 billion years ago.

Following those dramatic beginnings, life on Earth was pretty simple. Bacteria and single-celled organisms ruled this tiny blue dot for billions of years, and it was only relatively recently that more complex creatures rose up from the sea and began to evolve on land on the supercontinent of Pangaea. The most famous of those creatures existed for 180 million years, from approximately 250 to 65 million years ago during a period we call the Mesozoic Era — otherwise known as the age of the dinosaurs.

It might have been the animated series The Land Before Time, released in 1988, that initially sparked my interest in dinosaurs as a young child, but after the original Jurassic Park came out in 1993, I was totally hooked. Imagining those fantastic beasts roaming the land was incredible to me, and for the next several years I became completely obsessed. I was convinced that one day when I grew up I would become a paleontologist, spending my career out in the desert meticulously uncovering the secrets of history in the fossilized remnants of giant prehistoric reptiles.

I never did become a paleontologist, but my fascination with the dinosaurs is still alive and well, and it would become the inspiration for our next great motorcycle adventure. The destination: Dinosaur National Monument, a hidden gem tucked away at the northern border of Utah and Colorado. Initially preserved in 1915 to protect the 80 acres surrounding its world-famous dinosaur quarry, the monument was later expanded in 1938 to include and preserve the 210,844 acres of desert, canyons, rivers and wilderness that would guide us on a two-wheeled journey through time.

Joining me on this ride would be my longtime friends Jimmy Bowron and Derek Mayberry. The three of us have shared many roads together over the last several years, and we’ve become great partners in adventure. We’ve logged countless miles with just as many stories to tell, and there’s countless more to come, I’m sure.

For this particular journey we assembled an eclectic group of bikes. Derek would saddle up on an ’80s model NX650 that he’s been fixing up. I would be riding the XR650L I recently built with technology born in the ’90s, and Jimmy would be on his sleek, modern Triumph T100. Different beasts from different eras, like the various dinosaurs of the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.

We hit the road in mid-July at the peak of summer. The days were long and hot, and we’d be facing triple-digit temperatures in the afternoons. The wind felt like riding straight into a furnace, and the heat coming up from our air-cooled machines only added to the steady stream of sweat beading down our backs. At one point in the middle of the Utah desert, I laughed in my helmet and thought to myself, “This must be how the dinosaurs felt when an asteroid came down and scorched them to a crisp.”

To beat the heat, I plotted a route that would guide us along the Yampa River and the Green River so that we could plan our stops around various places to cool down. From watering hole to watering hole, life source to life source, our need for H2O on this trip became a vivid illustration of its incredible importance for life. It has been an essential element for all living things for the last 3.6 billion years, and humans need it for survival just as the dinosaurs once did.

On night one we found the perfect spot to set up our tents in a soft, grassy patch under some trees at the edge of the Yampa River. After a quick dip in the water to clean up and cool off, Jimmy and Derek zipped up their tents and went to bed. The sun sets late this time of year west of the Rockies, and I stayed up for a few more minutes to watch the sky fade to a deep purple. I looked out on the horizon and imagined what it would be like to see some Brontosaurus grazing on the trees in the distance. I thought about how different the world might have looked back then, and how strange it is that we can gaze up and see the same stars as those incredible creatures that lived here millions of years ago.

Morning came quick and I brewed some coffee for the boys as we packed up the bikes and watched the sun rise over the Yampa. We hit the road early and made our way deeper into the desert. It felt like we were cowboys riding through the Old West on our steel ponies down a dusty trail of bones, drifting farther and farther into the desert abyss. Through sand and cacti and past the occasional animal carcass, the landscape was transforming into a barren nothingness, until eventually we arrived at one of the most unusual geologic formations in the world.

This 10-acre site was originally discovered by an early explorer and paleontologist named Earl Douglas, who published the first photographs of the area in 1909. He called it “The Devils Playground,” but these days the Bureau of Land Management has named it “Fantasy Canyon.” It’s a great name because as you explore, your mind can’t help but wander into fantasy. I thought the walls looked like a pile of dinosaur bones, and I told the boys that it felt like we were walking around on Tatooine. But Derek had a more accurate description, saying that it felt to him like this place used to be an underwater oasis. It turns out he was right: This canyon was formed on the east bank of a massive 120-mile-wide lake called Lake Uinta. Formed around 50 million years ago, shortly after the dinosaurs went extinct, Fantasy Canyon is filled with widely scattered bones from various mammals and turtles dating back to the Eocene Epoch.

As we climbed up to the top of the canyon, Jimmy looked out on the horizon and spotted a group of wild horses walking atop a ridge in the distance. It was a picture-perfect moment to witness these majestic animals and just appreciate their natural power and beauty. But if we had happened to be standing here 80 million years ago, that could have easily been a group of velociraptors, and this moment would suddenly have felt much more terrifying.

After a quick pit stop to cool down in the Green River, we rode north another 40 miles to the world-famous wall of bones, located in the Quarry Exhibit Hall at Dinosaur National Monument. The rock wall contains over 1,500 exposed, fossilized dinosaur bones, including those of Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus and several others. This incredible wall of bones was also discovered by Earl Douglas in 1909 — the same paleontologist and explorer who discovered Fantasy Canyon in that same year.

Once upon a time, there was a river running through here where those dinosaurs would gather to drink water. But as the shrinking river slowly dried up, the animals died, and when the next monsoon came it washed their bones to this particular spot and preserved them in the mud. This wall of bones holds a map of Earth’s history, and a glimpse into another world long before human life, millions of years of history sealed in the bedrock. We are extremely lucky to be able to observe this history, and it makes me wonder how many incredible creatures were never preserved in the mud, and what kind of fantastical beasts once lived on Earth that we will never know about?

These were some fun ideas to contemplate on our ride out to the next camp spot. Winding dirt roads guided us through a spectacular canyon lined with rock formations jutting up from the surface, with sharp and jagged features resembling the jaws of a Tyrannosaurus. I really enjoy these remote destinations because they give you the time and space to ponder deeper questions about life, who we are, what came before us and what might come after.

Then, a mile before reaching our final destination, we stumbled on a more recent artifact of history, only this time it came from humans. It was a beautiful wall of petroglyphs featuring ancient Native American artwork from over 12,000 years ago. The history of life on our planet is a mysterious puzzle, and the more artifacts we continue to discover, the more puzzle pieces we will have to paint a picture of the past.

Day two ended with another sunset swim in the river as the three of us laughed and howled, sending echoes for miles down the canyon. I’m thankful to be here with these boys, and I feel lucky that we get to exist together in the same tiny moment of history. The following morning would rise to a blood-red sun, and we would begin the long ride back to reality. But for now we can live here, in this moment.