Friendship and Hardship From Montana to Oregon

Words and photography by Max Marty

I never really knew my neighbors here in Kila, Montana, until recently, when I met Logan Vaughn. Logan and I went to the same high school, but we only officially met this year and have become fast friends ever since. Logan enjoys working with his hands, and he is currently building a log cabin and fixing up an old sailboat. I’m a photographer by trade, but I also enjoy building things, too, so together we took a job in Oregon outfitting out a custom Ford Transit van for a local company. It would be a fun job with my new friend, but we had no idea that our time spent out there would spark the idea for a return on two wheels, and an unforgettable adventure that would ensue from our homes in Montana to the Oregon coast and back.

On that job in early April, Logan and I were driving one loamy dirt road after another. The roads angled up and away through misty forests of impossibly tall cedar trees. There were winding creeks with bordering hot springs and patches of ferns and moss so thick you just had to lie in them. It felt like a motorcycle adventurer’s paradise, but unfortunately, we were on a job with a tight schedule and confined to the cockpit of the Transit van.

For two young, Montana-raised boys, it was humorous to be in such a beautiful new environment, surrounded by the inspiring wilderness and trapped behind a windshield like wild animals in a cage. It wasn’t right, and we wanted to make it so. We both turned 21 this year, and together we decided that we would celebrate by making a return on motorcycles, taking mostly dirt roads to get there. The following week we returned home, made our plans, prepped our DR650s and hit the road a few days later.

The first stretch of the trip was a brutal affair. My bike was slowly rattling apart, and as I replaced the countless nuts and bolts one by one, it began to feel like I might do a complete rebuild using Ace Hardware parts from various small towns. Then my 70-200 camera lens fell off my bike, over a cliff, and down 75 feet into the Koocanusa Reservoir in Montana. I was being taken to the cleaners.

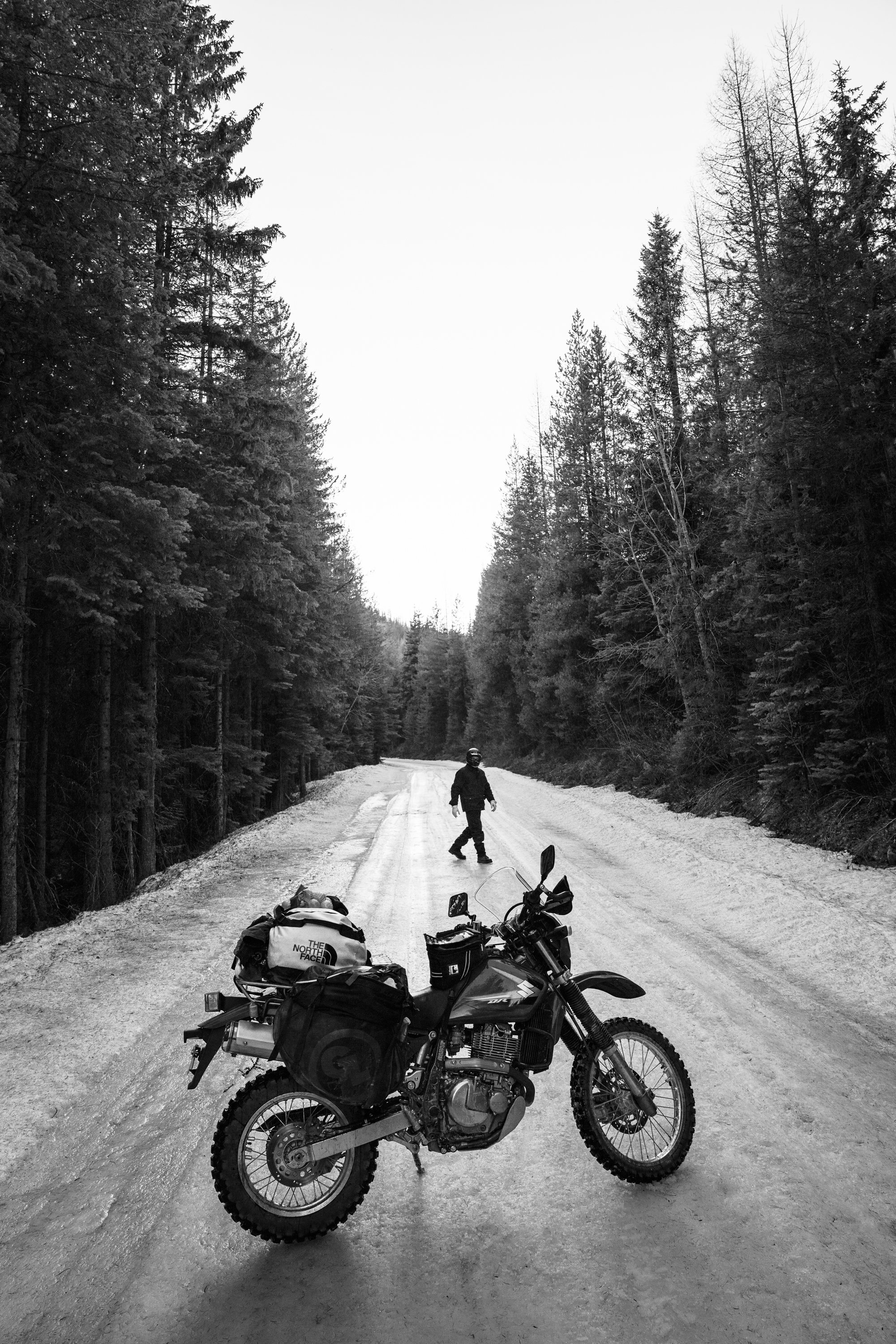

Much of the roads in Montana were still covered in ice and mud. Riding was slow and tedious, and this was starting to feel less like a celebration and more like some sort of punishment. We averaged 60 to 90 miles per day, and almost every dirt road we took led us through snow so deep you couldn’t see the wheels of the bikes. We were feeling worn and weary, and setting up and taking down camp was a brutal affair because the weather was poor most nights. We rarely had any idea of where or when we’d camp, and finding old wooden sheds or decommissioned fire lookouts became the norm.

There was one night that stood out in particular, in Northern Washington, when we decided to ride up to a fire lookout that we saw off in the distance. Shortly after taking a ferry across the Columbia River, we started gaining elevation, and with every switchback the road began to disappear under a blanket of deeper and deeper snow. This time, though, it became so deep that the road was impassable on our bikes. Logan’s theory was to take a downed tree and lay the most flat and uniform section on the snow to ride over it, then repeat until we reached our shelter. Although bizarre, it made sense, and it worked. Lewis and Clark would have been proud. Inch by inch we finally made it to shelter, crawled into bed and slept for two days.

Often during this trip, in the later hours of the day, our dwindling appreciation for these moments would spill out and paint a picture of excitement for life. A strange feeling of thankfulness for the long and tiring days on the road and the feeling of accomplishment after getting through it. It is so refreshing to escape the rat race and reset, if only for a moment. And to do it all with my new friend and neighbor, Logan.

We made it to the Oregon coast on day ten with the town of Seaside harboring our finish line. Logan and I sat quietly on a cliff, eating sandwiches and watching the sun set over the Pacific. We shared eagerness for the next day, and went so far as the next year. We slept underneath a picnic table that night as it rained, and I laid there reminiscing on what an unforgettable ride it had been, wishing it didn’t have to end. And that’s when it struck me. We still had to ride back to Montana. Another ten days.